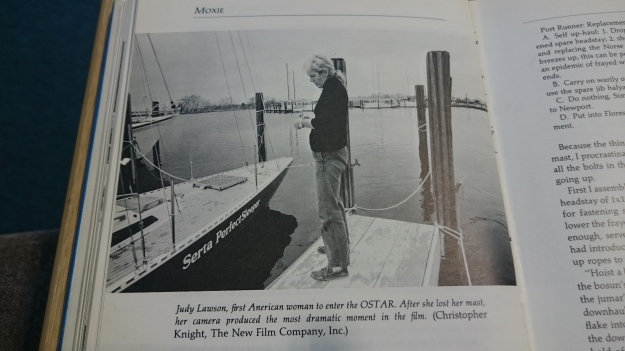

There may be a good time and place to lose a rig and a large chunk of deck and main bulkhead, but 130 miles off the northwest corner of Spain in a full gale on a pitch black night is definitely not it. Still, it could have been worse…

Destination Winter Sun

The morning of Tuesday 13 October found me alone in the bar at the Cowes Corinthian Yacht Club, getting one last wi-fi fix on my laptop. David Bedford, world class sailor and coach, wandered in and seemed surprised to find me there. I’d first met him some months before when I’d helped out on a GBR Blind Sailing Team training weekend. Today he was coaching a team of paralympic hopefuls. He asked if I wanted to come help him on the RIB, and I took great delight in answering “can’t today, sailing for Lanzarote”. “What are you doing here then? You’ve got the perfect wind for it!” He had a point. The brisk, if chilly, northeasterly had been blowing for days, and would not last forever. “Just a few more bills to pay, weather files to download and errands to run, then we’ll go out with the tide” I assured him.

By three o’clock in the afternoon we’d filled the water and diesel tanks and, without any fanfare, motored out of the Medina and hung a left toward sun and fun. I have often heard sailors remark that it is a relief to finally get to sea after all the hectic preparations for a long passage. This was doubly true for Rupert and me now, because prior to all the endless lists we worked through to get ready for our planned Atlantic circuit, we had had a full-on racing season, including a double-handed Rolex Fastnet campaign and the Red Ensign Azores and Back Race. While we’d not won any silverware, we were reasonably happy with our performance throughout this, our first season taking part in the Royal Ocean Racing Club’s offshore series. We had more than held our own against many bigger and better funded boats. I was also particularly pleased to have completed the return leg of the AZAB singlehanded, thus qualifying to take part in the 2017 Original Single-handed Trans-Atlantic Race.

The new Wind Pilot was working a treat as we left the Needles in our wake

We had petitioned the RORC to let us compete in their Transatlantic Race (departing Lanzarote for Grenada in late November) despite being marginally outside the permitted rating band, but while waiting for their decision we decided that we would prefer to make a more leisurely crossing, and pick up racing again once we reached the Caribbean. In winter 2007/8, before I met Rupert, I had crossed the Atlantic as a crew member on a 40 foot classic teak yawl, sailing from the Canaries to Brazil via Senegal and Cabo Verde. I had enjoyed the stops along the way, and was keen to share some of these places with Rupert.

Four days out of Cowes, not long after sunset, Rupert and I were sat next to each other on the starboard settee. I had just cooked a vegetable stir fry and we were waiting for the rice to be ready. One of the cabin lights was on, enough for me to see what I was doing in the galley, but not so much that it would interfere with Rupert’s night vision, allowing him to stick his head out of the main hatch every 10 minutes or so to quickly scan for traffic and check that all was well on deck. We’d not seen any traffic since passing the Irish flagged trawler Skellig Light II in the small hours of the morning.

The previous day had been livelier than anticipated, with a knockdown in only 28 knots, followed by building wind and sea state, but it seemed like we through the worst. We were officially well out of the infamous Bay of Biscay, well away from the continental shelf, and the wind was forecast to start moderating in about five hours. We’d dropped the mainsail entirely the day before, and after a night spent lying a hull, we’d been comfortably broad reaching all day under a small amount of headsail. The new wind vane steering was working impeccably, and we were making between 6 and 7.5 knots of boat speed with the wind and waves fine on the port quarter. Before it got dark we had spent around an hour studying the waves, and had concluded that it wasn’t necessary to deploy our Jordan Series Drogue. Now we were chatting about the sailing we were looking forward to, in sunshine, warmth and trade winds. It was a rare moment of cosy, relaxed togetherness, the sort of moment we were looking forward to sharing more of, now that we had decided to take a break from racing for a few months.

Impact

Our tête-à-tête was interrupted by the loud roar of a mammoth breaking wave on the port side, further forward than any previous waves. I remember us staring at each other with “WTF?!” looks and then both turning toward the sound. There followed an even louder bang, accompanied by the sickening sound of tearing wood as we were hit by the wave. The lights went out and the boat felt as it if had been thrown sideways to starboard. There was likely some swearing, and then Rupert asked me to hand him a torch from next to the chart table. The saloon table, which is normally stowed upright against the main bulkhead when at sea, had fallen down on its hinge. Rupert took the torch and moved the table out of the way in order to examine the area from which the noise had come. “There’s a bloody great hole in the boat!” he said. “Don’t be melodramatic” I replied, picturing a hole the size of a few square inches at most. “I’m serious! Check the rig!” he replied. I grabbed another torch, threw forward the main hatch, and stuck my head out. In the beam of the torch I could see that our mast had been broken about two meters above the deck, and most of it was now hanging over the starboard side of the boat, attached by numerous shrouds, stays and lines. “The rig is down” I reported, although it was hardly a surprise at this point, “it’s resting against the side of the hull, but I don’t think it’s in danger of holing it.” I then popped my head out of the hatch again and trained the torch on the port side deck. I got my first glimpse of what Rupert was on about: a two meter long piece of the side deck had been ripped out from the boat, and was resting about 9 inches above where it should be. “Holy shit” was the phrase that sprang to mind.

damage to deck as see from the pontoon, looking aft

Keep Calm, Carry On

“What do we do? Do we need to get ready for a possible abandon? Should I activate the EPIRB? Or at least inform Falmouth Coastguard?” I was sat still on the engine box but had the odd sensation that I was sprinting in circles. Rupert had been assessing the situation below “I think we’re going to be okay, there’s almost no water coming in through the hole. I’m going to have a look on deck.” Despite his reassurances, I thought it wouldn’t hurt to prepare for abandoning, just in case. Unusually for us, we had not put our passports and the boat papers into our emergency grab-bag at the start of the passage, so I did this now. To it I added our mobile phones, portable charging devices and the Iridium Go satellite communication device. I started to fill another dry bag with things it would be nice not to lose, such as our laptops.

Rupert came below and informed me that he had knocked the pins out which were connecting the shrouds to the chain plate on the port side. This greatly reduced the risk of the torn bit of deck being lost overboard. The mast was then being supported by internal halyards, with the torn end of the upper bit portion of the mast still above deck level. Rupert went onto the foredeck via the fore hatch and cut those. From inside the cabin I could hear the broken end of the mast scraping down the outside of the hull as each halyard was severed. I reported this to Rupert, and suggested that the backstay and runners could do with cutting. He then returned to the cockpit via the cabin to do so, and he cut the impeller line for the towed generator as well. He took the pin out of the cap shroud on the starboard side, and this left the starboard lower shroud under too much load to knock out the pin holding it to the chainplate. This shroud, like most of our standing rigging, was 10mm Dyform. That is to say, even with the most expensive hydraulically-assisted wire cutters, in the most relaxed of circumstances, it would be difficult to cut. Luckily, our friend Rudy had suggested that we carry a cordless angle grinder as part of our safety equipment for just this eventuality, and we did so. It did the job flawlessly. The rig was then attached to the boat by the forestay (which still had the part-furled cruising genoa on it) and it was acting as a sea anchor. The boat was lying head to the seas, drifting slowly downwind, and, most importantly, not taking water over the deck. We managed to lash the piece of broken deck and bulkhead to a u-bolt at the base of the main bulkhead to prevent it getting blown or washed away. We then stuffed all five of our spinnakers (in bags), fenders, spare pillows, you name it, into the gaps to slow any water that managed to find its way in.

We connected the emergency VHF aerial and then I reheated our dinner. Unsurprisingly, neither of us had much of an appetite at that point. While the memories were still fresh, we wrote up an account of the events for the logbook. I then offered to take the first watch. Rupert crashed out on the beanbag, while I tried to relax with a novel and some music on my iPod. I discovered the iPod had a periodic alarm feature I’d not noticed before. I set it to go off every 15 minutes, reminding me to go have a look outside. I had just started reading “Cutting for Stone”, and one of the early chapters described a character’s thoughts, feelings and regrets as she prepared for a crash landing on an airplane with engine failure. I admit I got a bit emotional at reading that, as it encouraged me to think about my own life in similar terms. Had I made the most of it? Were there people who would never know how much they meant to me if we didn’t manage to get out of this situation?

deck damage, as seen from the heads, looking aft

On my first off watch I struggled to sleep. I could feel a cool draught on my face from the hole in the deck. I thought of various of my sailing heroes who had survived much worse than this – the Smeetons and John GuzzweIl aboard Tzu Hang off Cape Horn, David Lewis on Ice Bird off Antarctica – and gained comfort and hope from this. I rested on the beanbag for a couple of hours, periodically opening my eyes to see Rupert perched on the engine box in front of the chart table, studying the chart and pilot book entries for ports in northwest Spain. I thought about how lucky I was not to be having to deal with this on my own, and also how fortunate that the other person was him, a former Yachtmaster Instructor who had been through a dismasting before, and had recently co-authored a book about managing risk at sea. I was getting a masterclass in sea survival.

By 0400 I was back on watch. Shortly after crashing out again on the beanbag, Rupert jumped up suddenly, muttering something about noises and the main halyard. The legendary ‘skipper’s ear’ in action. He put on his boots and lifejacket and went on deck. He returned a few minutes later and explained that he had forgotten to cut the main halyard from the head of the sail, which was flaked on the boom, and was therefore at risk of being dragged into the water. Likewise, he’d forgotten to cut the jib sheets, which were still running from the sail (underwater) to the jib cars on deck. To my shame, I’d not thought of those either. Having sorted those, he flopped back down on the beanbag and was snoring again in a matter of minutes.

I studied the chart a bit before returning to my calming music and novel between my regular checks for things outside. We continued to drift between 1 and 2 knots, although our direction of drift changed from west of north to east. At about 0600 I saw a pair of ships traveling in the opposite direction to us off the port side, which was just as well, as of the pair of navigation side lights only the port side was functioning. They did not appear as AIS targets on my chart plotter, which led me to believe (incorrectly, it turns out) that our emergency antenna was not working. I estimated their CPA at 2 miles.

The Morning After

On my next off watch I was finally able to sleep relatively soundly. Rupert performed the routine engine checks and then woke me at first light. The wind was down to 10 knots from just south of west and there was very little cloud although there was still a residual swell. It was another world in the sun. Seabirds were circling behind us, probably taking us for a fishing vessel. I made a thermos of coffee for us to share and we set to work tidying up outside in preparation for motoring. It was absolutely imperative that we make sure there was nothing in the water that might foul the propellor. At some point in the night the forestay had finally broken, allowing the rig to sink to the bottom of the sea, and saving us the chore of having to cut it away. Still, it took us nearly two hours just to remove all the lines from their blocks and clutches and get them down below. It was sad work, as so many of the lines had been rendered no longer fit for the job due to having been cut. Eventually the cabin floor came to resemble a multi-coloured snake pit.

We checked and re-checked that there were no lines the water, and then I went below to start the engine. Rupert sat at the helm and gently put on some forward throttle, we were moving, but something wasn’t right. She wasn’t answering the helm. My stomach turned. Oh god, we hadn’t lost the rudder as well, had we? Rupert was quick to reassure me that we hadn’t, the rudder stock had simply been twisted with respect to the tiller. We would just need to hold the tiller to starboard in order to travel straight ahead and centrally to turn right. Turning left would just entail a 270 degree turn to the right. Sorted.

I then transferred my worries to the amount of water coming in through the hole in the deck. Surely motoring into the waves would cause more splashes to find their way in? I went below for my first bailing session. I scooped water from under the floorboards in the head, just forward of the main bulkhead, and poured it down the toilet. This is the one bit of the boat that required regular bailing even in port, as it was next to the heel of the mast and it was virtually impossible to stop water (usually rainwater) from flowing down the mast. I alternately filled and pumped out the toilet six times. I recorded this in the log, as if it was a lot, with a note about how we had not bailed since leaving Cowes, so who knew how much of this water was already there before the hole in the deck. Before long though I stopped counting the number of times I pumped in favour of just keeping track of how many minutes out of every hour we needed to pump to keep the water below the floorboards.

deck damage, seen from coachroof

Hello World

I then prepared some porridge for the two of us. It was probably the most memorable bowl of porridge I’d ever had: warm, filling, and bland. I did a bit of general tidying below, and then decided it was probably about time we let some people know what was up. I installed myself on the beanbag with a notebook and drafted an email to Falmouth Coastguard, the official first point of contact for British-registered vessels travelling beyond UK waters. I then stuck my head out of the companionway and read my draft to Rupert who suggested some changes. We were keen to communicate our situation without causing alarm, which was slightly challenging, as it was, to be fair, a pretty alarming situation. We knew that if a search and rescue effort was triggered we would most likely be compelled to take part in a physically risky evacuation procedure involving either a merchant vessel or a helicopter, and that Zest would be left to fend for herself. Both of these possibilities were best avoided. We eventually sent the following:

To: falmouthcoastguard@mcga.gov.uk

Subject: Yacht Zest incident

SUMMARY

Yacht Zest, callsign MPZQ9, MMSI 235099501, CG66 ref 85906687

dismasted approximately 130 nm west of La Coruña

current position: 43 592.N 010 48.7W

on board: Kathryn Schmitt and Rupert Holmes

current status: stable, but request monitoring.

BACKGROUND

At 2040 BST on Saturday 17 October in position 44 04N 011 06W we were dismasted as result of port chain plate carrying away. We cut the rig free.

On the morning of Sunday 18 October we started motoring toward La Coruña. The winds are forecast to increase tonight, at which point we intend to lie to a sea anchor (a Jordan Series Drogue). Once the wind moderates we intend to continue motoring to La Coruña, ETA Tuesday.

We are carrying an Iridium Go satellite phone +88162346548. Our Sea Me active radar reflector is still functioning. We have rigged an emergency antenna for the DSC VHF, and also have a handheld VHF. We are carrying an EPIRB and a PLB, but have not activated either.

To clarify, we are not asking for or expecting assistance at this time. We are expecting to make port under our own steam. We are able to provide frequent position updates via email if requested.

Kind regards,

Kathryn Schmitt and Rupert Holmes

The CG66 mentioned is a form that can be filed with the coastguard. It gives any details of your boat that might be helpful in a search and rescue situation, and provides shoreside contacts, a.k.a. next of kin details. Both Rupert and I had purposely provided names of friends who were not next of kin, but would know how to get in touch with our families if necessary. More importantly, our contacts knew enough about seafaring that they would not immediately panic upon getting a call from the coastguard. Just the same, we thought it prudent to give them a heads up, and sent a short but (we hoped) reassuring message to each of them. I would also struggle to think of the best way to reply to various routine messages from sailing friends, some of whom were not yet aware of our plight. My friend Deb, for example, wrote on Sunday evening describing a vegetarian lasagne she had just cooked that she reckoned I would enjoy. If she only knew how appealing that sounded to me just now, I thought. Jerry wanted to know how we were getting on with our new wind pilot (A: great! until the vane was ripped off by the wave). My friend James Taylor continued to act as our main point of contact on land, a position he had voluntarily assumed when we left Cowes. He was in touch with the coastguard to confirm that my email had reached them, as I had found several different addresses for them and was not sure which to use. He also liaised with my insurers, who said they intended to send a representative to meet us in port.

Rupert and I continued to take turns driving, at a conservative speed of around 5 knots while there was daylight and benign conditions. We wanted to conserve fuel and minimise the risk of engine problems. Off watch, we tried to get as much rest as possible. Any other activities were ruthlessly prioritised. As darkness fell, Rupert rigged up the old bicolour navigation light to take its power from the 12V socket, and taped over the red half of it, as only our starboard navigation light had been damaged when the rig came down. At 2046 on Sunday, almost exactly 24 hours after the dismasting, we stopped the engine for about an hour. This was primarily to check everything on the engine was still working properly but also to have a break from the noise and the motion in order to reevaluate our plan. We studied some weather files. The wind was forecast to rise to beaufort force 8 from the east overnight. In light of this we decided it would make sense to turn more toward the south. This would allow us to gain shelter from the land sooner, and would also put us at a more favourable angle to the wind and waves. With that decided, we turned the engine back on and set off on our modified course. Once in the lee of the land we would have several options for ports. We identified Muros as the most promising, if not the closest, option as it appeared to have good shelter in all wind directions and space for anchoring if necessary. There were a number of closer ports in the Ria de Camariñas and Ria de Corcubion, but the approaches to and/or shelter in those appeared potentially iffy.

the hole, as seen from the cockpit, after most of the ‘stuffing’ removed

The Second Night

The next night was just as dark as the previous one, and the wind and waves seemed to want to match the previous night’s as well. I found driving increasingly nerve-wracking. More and more waves were striking the port side of the boat in front of or next to the hole, causing increasing amounts of water to get into the boat (not to mention occasionally over the person at the helm). I found myself wincing and swearing with every wave that hit. Also we were crossing the area where large numbers of ships funnel into and fan out of the Finisterre Traffic Separation Scheme. For much of this time both of us were needed in the cockpit: one to steer, and one to take bearings on ships with the hand bearing compass to determine if we were avoiding them. Basic competent crew stuff, but tricky when the seas are big and one is exhausted and slightly out of practice thanks to AIS. We had both our fixed and handheld VHFs on but heard little, if anything, on channel 16. This, combined with the lack of AIS targets on our plotter corresponding to the ships we could see, led us to conclude that our emergency antenna was not working. As a result, there were a couple of occasions where we temporarily reversed our course to get away from ships we weren’t sure we would clear. In retrospect, we may have been better off crossing the TSS itself, as the ships’ courses would have been more predictable there.

Once clear of the traffic we each got an opportunity to sleep for a couple of hours each. Monday dawned extremely windy and grey. Rupert shouted ‘land ho!’ but I struggled to see anything in the murk and big swell. The wind was gusting into the 50s, whipping the tops off the waves. By 0930 we were very glad to be in the lee of the northwest corner of Spain. More and more waves were finding the hole in the deck, and we were having to spend increasing portions of our time bailing and pumping. Whereas most of the water had been finding its way into the bilge compartments in the head, now a lot of it was going onto the port pipe cot and then flowing off that onto the port settee berth and from there into the bilge in the main cabin. It reminded me of some sort of demented water feature in a shopping centre. By this point the water in the bilge was splashing up through the spaces between the floorboards, so I stowed the beanbag and took up the floorboards for ease of bailing.

As we passed the first of the rias it was clear that the risks of turning into it far outweighed the rewards, so we continued south. As we approached Cape Finisterre we decided to pass on that ria as well. Just then we were surrounded by dolphins. I had rarely seen so many, nor had them visit for so long. They were spectacular, flying out of the faces of waves, sometimes above deck level. We also started to encounter local fishing vessels. One in particular frustrated me. It was crossing us from our starboard side. I altered course to starboard, as per the COLREGS, but it then altered its course to port, forcing me to go ever further to starboard and so on. I think they may simply have been rubbernecking, wanting to get a closer look at the yacht with no mast and a large hole in the side deck, but I just wanted to get to port. Why were they tormenting me like this! And why was I overreacting to such a trivial thing? I know: exhaustion.

We finally got clear of all the fishing boats and reached the turning for Ria Muros. Rupert took over on the helm and I went below to heat up some soup for lunch. The wind was funnelling down the ria. While this meant that if the engine failed now we would be blown safely back out to sea, it also meant that we were now pounding into the waves, with seawater continually raining through the hole in the deck. I went to bail and pump the heads compartment, but it seemed to be a losing battle. Thinking that we were on the home stretch, I had recently changed into my last set of dry thermals and mid layers, and they were now wet. Meanwhile the soup started burning, so I turned off the stove. I returned to the bailing and managed to sort out the heads compartment, by which point the main cabin bilge needed bailing. By the time I finally got on top of things the soup had gone cold and we were both getting grumpy. Rupert insisted we could turn around temporarily if the water level was getting too high, but we would just lose ground and have the same problem when we turned toward port again. It really was just a matter of toughing it through the final hurdles.

The Home Stretch

The mood improved after we’d had our soup and started to see the first signs that we really were near civilisation. We could make out cars on the road along the ria, and we could see windows on the houses. The tall hills on either side were covered in pine trees. It reminded us of some of the places we frequent on Rupert’s boat in northern Greece, and the feeling of homecoming, even if spurious, had a relaxing effect. We retrieved the red ensign and attached it as best we could to the starboard pushpit as its normal home on the backstay was temporarily unavailable. I searched through our collection of courtesy flags looking for the Spanish one, before remembering that when I had gone to buy one I had discovered there were two variants: one with a crown and one without. I had postponed that purchase until I could figure out which variant was the most appropriate, and then promptly forgot about it. I hoped in the circumstances we might be forgiven this breach of protocol.

We rounded Cabo Rebondiño and got our first glimpse of the breakwater at Muros, now only half a mile away. It had the usual assortment of blokes in hooded parkas fishing off of it. I called Marina Muros on the VHF to request a berth. No problem, the guy said, he’d meet us on the pontoon deportivo. Great! I thought. I relayed the message to Rupert in the cockpit, who asked if I knew exactly where that was. I didn’t. The marina was pretty new and the chartlet in our pilot book was not agreeing with what we could see. I tried to contact the marina guy again to get more detailed directions, but could not raise him. In the meantime we still had warps and fenders to put on, so Rupert kept the boat hovering just outside the harbour entrance while I sorted those. In the meantime a figure appeared amongst the anglers on the end of the quay shouting at us and gesturing. He was tracing a big S from the bottom to the top. We followed these instructions, motoring along a wave break pontoon and then making the bottom bend of the S, passed a bunch of what looked like hybrid fishing/dredging vessels before encountering another figure on the quay directing us to take a right and then the second right. We did so, and then saw the first guy again, standing on the pontoon directing us to a particular berth. We parked as instructed, by which time the second guy had arrived. It was approximately 16:30 local time on Monday 19th October. I stepped onto the pontoon and then got down on my hands and knees and kissed it. I then stood up and introduced myself to Pedro the marina manager and Manuel the port police officer with the sort of hugs and kisses one would give long lost brothers. I am not sure whether they were more surprised by this or the state of our boat. We answered their questions about what had happened, their eyes becoming more saucer-like with every detail. They then withdrew, with Pedro telling us we could come clear in whenever we were ready, no hurry.

the crack in the main bulkhead continued most of the way across the boat

And Relax…

We went below to savour the sensation of being safely alongside with the engine off. We looked at the wet mess surrounding us and thought “arrival drink”. The only alcohol we had on board was a bottle of Azorean white, and nice as it is, it didn’t appeal just then. There was a knock on the hull and we popped our heads out of the companionway. Klaus, the owner of a Vancouver 34 on the next pontoon, introduced himself. He said Pedro had told him our story and asked if he could help in any way. I thought a moment, and then asked if he had anything stronger than wine. Would Venezuelan rum would be okay? I told him it sounded perfect. He returned with a bottle a few minutes later and we invited him onboard to toast Zest and our safe arrival. That done, Klaus took his leave and I went to gather the documents we needed to clear in. I retrieved our passports from the grab bag, but was very worried not to find the ship’s registration with them. With growing panic, I searched all the places I thought it could be with no luck. Rupert assured me it would be fine, everything else was in order, they would surely understand.

We went ashore and found the small blue house Pedro had mentioned. Pedro ushered us into the office and began the formalities. We gave him our passports and he gave me a form to fill in. It was very similar to forms I had seen elsewhere, apart from one detail. Under the bit asking if my vessel was motor or sail, it then asked ‘if sail, how many masts?’. We shared a good laugh at that. As Rupert predicted, the lack of a ship’s registration document was no immediate concern to Pedro, as it was clear we weren’t about to go anywhere. In any event, I did find it the next day…in the grab bag. With the clearing in completed, he issued us with a set of keys for the house and the marina gates, and then gave us a tour of the house. It comprised of excellent showers for men and women; two lounges with comfortable sofas and decent wifi; a kitchen with fridge, freezer, microwave, washer and dryer; and an enclosed garden. He invited us to make ourselves at home, and I could see right away that this would not be difficult. There was well-stocked and friendly supermarket two minutes away, and next to that an ironmonger. By the next day we would discover an excellent bi-weekly market, a number of welcoming bar cafes and some new friends. It seemed we really had landed on our feet.

Some Lessons

* Be a safe stowage fanatic. ‘A place for everything and everything in its place’ is about much more than keeping tidy, it can save your life. We had become a bit complacent, habitually leaving our mobiles, the iPad and the Iridium Go unsecured on the chart table. In the knockdown they all went flying across to the galley. Luckily for us, the only damage was to the screen of Rupert’s phone, but had the iPad and/or Iridium Go been broken we would have had our communications severely limited.

* No really, check your stowage. Our precious angle grinder also managed to take flight across the cabin in the knockdown, despite (we thought) being securely lashed down under the chart table. Luckily (again) it was still working when we needed it the next day.

* Keep your safety procedures up to date. A great side-effect of taking part in the sort of racing we had been doing is the requirement to comply with the Offshore Special Regulations. It’s tempting to treat this as a box-ticking exercise, but it’s important not to. The OSRs provide a great framework for planning through how you would deal with a wide range of gear failures and emergency situations. They should be revisited frequently, especially when there is a change to any of your safety equipment. In our case, we neglected to notice that the modified mounting arrangement for our new life raft made it significantly more difficult to deploy our Jordan Series Drogue.

* Don’t panic. My guess is that 99% of sailors in our situation would have immediately activated their EPIRB, and had I been on my own I admit I would probably have been one of them. All credit to Rupert for keeping me calm while he did his rapid initial assessment of the damage to determine that we were not facing a mayday situation. Triggering a rescue might well have put us and the boat in even more danger.

mast damage seen from the port side